How to Understand Art - A Mark Rothko Case Study

The idea of taking your Tinder date to an art gallery sounds good in theory. But going there, looking at the paintings and thinking to yourself, "I don’t get this" isn't fulfilling.

Or you come across an article on the internet about some abstract painting selling for $20 million dollars and you go, "Wait, whaaaat?"

Or let's say you have developed an interest in the arts. Perhaps that Tinder date went well, and you want to make a grand gesture by gifting a painting. How do you decide which one is good to buy? After all, there is no manual which says that a painting in a certain style is superior than others.

You learn that 'good art' is subjective. Why then are some artists held in higher regard than the others? What is it about Picasso, Dali, Van Gogh and Da Vinci that makes them indisputable geniuses? If you are not an art connoisseur, how do you identify great art from bad? Or even before that, how do you understand what the artwork is about?

This post is my attempt to answer these questions by tackling the work of a painter I admire - Mark Rothko. Also covered are the topics ‘Why to understand Art at all’ and ‘The Business of Art.’

WHO IS MARK ROTHKO?

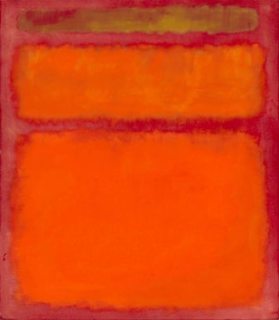

Rothko (1903-1970) was an American painter of Russian descent. The images below are some of his works:

This style (called 'multiforms' by critics)- large blurred fields of solid color devoid of any figures or symbols - was his signature work. His paintings often feature in the list of most expensive paintings. This one went for $188 million, this for $90.6 million and this for $84 million.

The small images here won't do justice to his work. But I've added them to give you a reference point for everything that follows.

WHY MARK ROTHKO

Falling in romantic love is instinctive rather than calculative. We fall in love with the whole human being and not just with the sum of their individual qualities. This is why we hear things like "I love him for what he is as a person," or "I love how she makes me feel." A piece of art is quite similar.

This is where our first lesson begins.

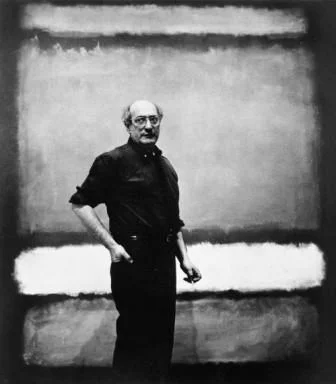

Mark Rothko in front of one his paintings

When I first looked at a Rothko, I was instantly captivated. I felt strong overwhelming emotions and a feeling of transcendence that I’ve experienced rarely. There was no rhyme or reason to my attraction towards it; there doesn't need to be any. Sometimes, a painting's job can just be to make a wall look better. Art's primary function is to be admired. It doesn't have to reveal a profound secret message to be worthy of appreciation.

So the simplest way to understand or judge a painting is to answer - Do you like it? And by 'like' I do not mean the technical qualities, but just enquiring whether it looks aesthetically attractive to you.

I chose Rothko because it appealed to me. The minimal language of his work goes well with my philosophy of life. But there is no need for you to feel the same way to understand it. Perhaps you even had a few questions like:

Why is it so famous?

What am I supposed to understand?

What's the meaning of this?

Isn't this very easy to make?

This was sold for $50 million dollars! Is this real life?

All these are valid questions which deserve an intelligent response. But that is for later. For now, all we need to do is simply answer the ‘Do you like it?’ question. Do you think it looks good? Keep the doubts for later and just observe without any notions about what it may or may not mean.

FORM AND CONTENT

Lesson number two.

After the initial reaction, it is a good idea to look at the form, the painting itself: The canvas frame, color palette, the subject, shapes, brush strokes, layers. Imagine how it was done, how it could be done.

Rothko used large canvases

In the case of Rothko, you notice the simplicity and the deliberate lack of any symbolic reference. You notice the depth and intensity of colors, how there is a luminous quality to them. Or how the canvas seems much bigger than it is. You imagine that working on this painting would have been physically taxing for the artist.

You notice the patterns in all his work. Big rectangular boxes filled with deep colors in a flat picture plane - the boxes which appear to hover in and out of the picture plane.

Slowly the painting unravels a bit more. Numerous layers over layers of paint. The blue slightly visible behind the predominantly burgundy box. Or the green superimposed over the red. You notice these less evident colors at the edges or through the thin layers of the primary paint. This unravelling is like watching the artist’s process of creation in reverse chronological order.

You notice the name of the paintings and are surprised to see that most of them are titled 'Untitled' or 'No. X' or 'Orange, Red and Blue'. You sense the artist's deliberate attempt to avoid shoving his ideas towards the observer. It is what it is.

You hear someone telling a story of how when a journalist asked Rothko to explain his paintings, he said, "Silence is so accurate." You sneer at this artsy-fartsy statement. But then you have a longer look at the painting. And you realise that what he said might make sense to some. The paintings really don't say anything specific. Silence could be accurate. Your head spins a bit. You move on.

Of course all this is more apparent when you can see it in person. Rothko himself recommended that viewers position themselves as little as eighteen inches away from the canvas to experience "a sense of intimacy, awe, a transcendence of the individual and a sense of the unknown." People recount of experience of being engulfed by the painting or becoming a part of it. The barrier between the art and the audience vanishes.

The lack of frames on his pictures is because of this reason. According to Rothko, framing a painting implies that there exists a different reality in the work. But he did not distinguish between the canvas and the world outside. The intention was to "eliminate all obstacles between the painter and the idea and between the idea and the observer."

"I also hang the largest pictures so that they must be first encountered at close quarters, so that the first experience is to be within the picture. This may well give the key to the observer of the ideal relationship between himself and the rest of the pictures." - Rothko

Once you do this observation, you start associating certain qualities to the painting. A little more understanding is achieved merely by looking at it for longer than a few seconds.

Art often serves as a reflection of our times and the artist's personal exploration of her own identity around the zeitgeist. Thus, the next step in our understanding will come from the history and the context. For this, we have to go beyond the canvas.

BEYOND THE CANVAS - THE CONTEXT

Rothko's early work was much different from his later style. Some of his early work:

This was followed by a phase of transition to the multiforms:

This progression tells us a story of an artist who experimented with different styles before finding one which resonated with him. It teaches us one more thing - the debunking of the overnight genius myth.

Rothko’s final style of multiform wasn't an overnight spur of the moment decision. It wasn't on a whim that he decided to paint something like this. It took him years to perfect a style with which he could express all that he wanted to. It was as if he was learning this new style by trial and error. A method to madness, if you will.

The notions often associated with artists of making something totally random or esoteric or pretentious are thus invalidated in case of Rothko. After all, we have to ask ourselves, what was that thing that drove an artist who was as skilful as he was, to find a style which looks so simple and continue doing it for the rest of his life. What was this conviction in purpose, and where did he find it from?

In Rothko, we had an artist who broke away from the status quo, created a new style which was radically different from everything else at the time, and had the conviction and self-belief to persevere even in the face of doubters and naysayers.

Rothko Chapel

Thus, when you are looking at a Rothko, you are also looking at the result of conviction in purpose, thousands of hours of experimentation, rejection, and perseverance. If you want to take anything from his work, that in itself is enough.

The originality of his style is also something to be cherished upon. Most of what we do, the words I write, the person we are - is influenced by something external -the people we meet, the books we read, the places we go to. So when we find true originality, it should be celebrated.

In the book 'The Artist's Way', the author says of writing which I think is true for most art - we are conduits for the art to flow through us onto the canvas/paper. An artist’s job thus becomes that of a passageway rather than that of a glorified creator. In a life filled with mundane activities, this makes it a way of accessing the divine.

While drawing his pictures, or while imagining them, Rothko experienced this spiritual feeling. And this is what he wants to convey through his pictures. If we look at the pictures and search for a meaning in the shapes or the exact color used, we won't find it. This was abstract art, and abstract by definition means "existing in thought or as an idea but not having a physical or concrete existence." or "relating to or denoting art that does not attempt to represent external reality, but rather seeks to achieve its effect using shapes, colours, and textures."

If you are thinking that this is becoming tangential and bordering on the line of some spiritual bullshit, you are forgiven. It is fair to ask what is this 'spiritual feeling' that Rothko wanted to express. How do we understand it? This is where the next part comes, which to me is the most important bit of this whole post.

ART AND AUDIENCE

"The most interesting painting is one that expresses more of what one thinks than of what one sees." - Rothko

This section is about you. Not the collective pronoun 'you' who are all the readers. But 'You', the individual reading this post while taking a break from work, or on the Uber ride back to home, or while browsing your Facebook feed in the toilet.

Art needs audience. And each individual in that audience gives that art a different meaning. Without an audience to ascribe meaning to it, the art would lose its purpose. A great book is nothing but ink on paper if it doesn't inspire or entertain or make someone laugh.

Let me give you an example.

I am a big fan of Linkin Park and always will be. They might be passe now, but I will always have a fond memory of them. Music has been a great influence in my life. It has played a large role in shaping me the way I am. And Linkin Park was my gateway drug into music. They were probably the first band through which I was introduced to western music. I studied for hours in a dingy, smelly room while preparing for IIT entrance exam - their music kept me awake. I have sang aloud with friends while 'Numb' played in a rental car's shitty audio system while on a trip to Goa. I have played it on repeat on speakers in college until someone came and lent me a different CD or took their CD player away.

The point is that I have associated Linkin Park with my memories. And it is I who created those associations. And these links can be different for others. It might have been a way to deal with teenage angst for a kid growing up, or a guy who met his future wife at a LP concert might associate it with love.

Great art isn't great just for what it is. It is great for what it does to you, the changes it brings about. It becomes part of the moments of your life. It shapes them.

The meaning that we seek in life, the purpose and the singular reason for which we do the things we do everyday isn't to be found in a textbook, or on an inscription in a cave wall, or in the careless depths of LSD infused trance. Or even in a Mark Rothko painting. It is to be found within us, and in our understanding of the world around us. That meaning is what we choose to ascribe to things in our life.

If we decide to accumulate as much money as possible, then that's our meaning of life. If we decide to uplift the poor to a better state of living, then that's our meaning. Great art, like Rothko for me, gives meaning to my existence and the things I do. Or put it another way, it is I who decides what that painting will do to me. It is empowering.

It is I who decides to find meaning and understanding in this quote by Rothko -

"Small pictures since the Renaissance are like novels; large pictures are like dramas in which one participates in a direct way."

It is I who chooses to say ‘true that’ to this quote by him -

"If you are only moved by color relationships, you are missing the point. I am interested in expressing the big emotions - tragedy, ecstasy, doom, and so on. And the fact that a lot of people break down and cry when confronted with my pictures shows that I can communicate those basic human emotions… The people who weep before my pictures are having the same religious experience I had when I painted them. And if you, as you say, are moved only by their color relationship, then you miss the point."

Or in this one -

"Shapes have no direct association with any particular visible experience, but in them, one recognizes the principle and passion of organisms."

WHY TO UNDERSTAND ART AT ALL

There are three reasons for me in the increasing order of complexity.

1. “I think you want to learn about art because you had an experience of some sort - a totally non-redemptive but vaguely exciting experience, like brushing up against a girl with big boobs in the subway."

- David Hickey, Art Critic/Journalist/Writer.

If you ignore the slightly sexist comment, you can see what this guy means here. It is just a way to make you a more rounded person. Learning about why an artist, Picasso for example, is called a genius, never hurt one anyone right? Call it curiosity to understand this facet of life.

2. "The purpose of art is washing the dust of daily life off our souls."

- Pablo Picasso

For me, art is therapeutic. If I have a bad day, a day filled with art exploration usually recharges me. In fact, I have been struggling with work for the past one week. And today's act of writing this post has already made me feel much better.

Painting is slow art. You cannot look at it for 5 seconds and declare it good or bad. In a way it is very similar to poetry. (If you haven't picked Tagore's Gitanjali and wondered about the meaning of life after reading just a few lines, you are missing an experience). So in a world where the food is fast, news is breaking, and peace is ephemeral, art brings about a good change of pace.

3. Art is a way to express the inexplicable. Presumably, we’ve all experienced moments of transcendence whether on drugs or meditation or during our travels or in near-death experiences. Art, from what I understand is a way to explain that, to express emotions that words cannot.

THE BUSINESS OF ART

Although it doesn't have a lot to do with understanding Art itself, I want to touch upon this issue briefly because this is something which turns people off away from the art world.

A few years ago, when I had absolutely no idea about what art is, I came cross Joan Miro's “Peinture (Etoile Bleue)” which was sold for 37 million dollars. I scoffed at the price since it was something I thought I could paint. It was natural to assume that the art world is delusional or pretentious or both. But during the course of the research for this post I understood something else.

The art market isn't a reflection of who the best painter is. The highest priced painting doesn't mean the best painting. Buying and selling art is a business. And the prices in a business are driven by many other factors than just the quality of the work. If you can't fathom why a certain painting was sold for multi million dollars, that's fine. But, don't let its price discourage you from appreciating it.

Oscar Wilde said it best:

“A work of art is useless as a flower is useless. A flower blossoms for its own joy. We gain a moment of joy by looking at it. That is all that is to be said about our relations to flowers. Of course man may sell the flower, and so make it useful to him, but this has nothing to do with the flower. It is not part of its essence. It is accidental. It is a misuse.”

Conclusion

Abstract art isn't supposed to make you feel a particular way. It is supposed to help you embrace whatever it is that it invokes.

This 'something' could be different for different people. Great art incites conversations, discussions and conflicts of opinions. Rothko's work inspired me to write this post, so you could say I found inspiration and contemplation in his paintings. Perhaps you could find love, or reflection, or celebration.

If you look at any piece of work and wonder - "I could do that," you are missing the point. Good art is not judged by how difficult it is to make. Or the level of technical skill involved. Or the most skilful execution. And that is why it's subjective. This can be found in other art forms too. Hemingway didn't write the most complicated sentences, but he was a masterful storyteller.

Art may seem unapproachable at times. But if you give it a chance, it can turn out to be deeply personal and enriching.

Thank you for reading. I hope you ascribe positive association to this post in your life. And may that date at the art gallery become an important moment in your story.

If you liked this article, leave your email address here and I’ll let you know whenever I write something new.

More resources on Art and Rothko:

![Entrance to Subway [Subway Scene],1938](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/54326acbe4b0331aac16f283/1490711154470-YD6QXUJZQ79KCKM77JPP/Entrance+to+Subway+%5BSubway+Scene%5D%2C1938.jpg)

![Underground Fantasy [Subway], c. 1940,](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/54326acbe4b0331aac16f283/1490711204382-PD4FTYR9CA275XW93ABH/Underground+Fantasy+%5BSubway%5D%2C+c.+1940%2C.jpg)

![Untitled [Multiform],1948.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/54326acbe4b0331aac16f283/1488464887255-H3PPPD4A41HMB9XXOA31/Untitled+%5BMultiform%5D%2C1948.jpg)